Violet Bond: Bodies of Water

17 May – 27 July 2024

Bodies of Water

What challenges do you face as an artist living in remote locations in Arnhem Land, and how have you overcome them?

A major obstacle when living remote is access to opportunities, this is not only true for the art space but for kids at school, employment in communities, health care and many other realities when living bush. There is always a balance for me in my art practice – the deep appreciation and privilege of living on Indigenous land with Indigenous people while being afforded the ability to be inspired by some of the most remote, wild and beautiful places in the world coupled with the deep sense of privilege, frustration and often anger that comes with the so many injustices in Australians appalling track-record with its First Nations people.

I’ve always talked about the complex relationship I have with working in the environment as a white woman on stolen land and acknowledging the truth of that history while also trying to create work that is inspiring and hopes to connect its audience with their own environment and wilderness.

The digital art space has been the biggest opportunity for me and my art career to date. From using Instagram to promote my wild clay ceramics while on Kunabidji country in Maningrida or using NFTs to create performance works in the environment at Bulman, becoming part of the global digital art community has allowed me to break down the barriers faced by many artists currently working in Remote Australia and allowed be to show my works across the world.

How important is it to keep close to your roots and stay connected to the NT?

There is just nowhere like the NT for me. The reality is that here, nature is literally trying to kill you and we amalgamate these realities and that ‘realness’ into our everyday lives.

The NT also grapples with so many parts of the Australian identity, Indigenous Australia and the realities of colonisation alongside the cattle industry and fourth generation Chinese families; this melting pot of cultures, complex, difficult but real and connected is something I love about the Top End. Not to mention every dirt road and every crocodile is endless inspiration for me.

Your photographic, video and installation work has developed from your environmental sculpture and wild earth ceramics practice. How did that evolution come about?

I actually started out by creating sculptures from bones and feathers and that led to working with wild earth and through that I came to NFTs. But at my core I am always a photographer. The first time I developed film in a darkroom I knew it was a magic that I wanted to do for the rest of my life. The video works, I have always seen more as moving photos than films, single moments or fragments of moments rather than a story with a beginning, middle and end.

Someone said to me once “Oh so now you are the Pot”. I think that was the best explanation of the move to performance and photography from ceramics.

I never got into ceramics to fire work and sell ‘pottery’. I got into ceramics to make clay from the dirt, to pull something out of the ground that was deeply of its place. Recently, I have been doing that with my body rather than a wheel.

Do you have any plans to get back to the wheel and kiln to produce sculptural and ceramic works?

I do but they will probably be more ephemeral, muddy sculptures that can be returned to the dirt in the rain or clay and on skin that can wash away – or as is the case with this show, an installation work that has at its core the idea of disappearing and seasonal change and the impermanence of all things.

What is your favourite Top End season and why?

Unsurprisingly, it would be the two most ‘extreme’ ones. The very depth of the wet season, thunder storms, wild grey seas, jellyfish and deep, murky rivers. And the late dry season when all the countryside is blackened and nothing remains but charcoal and the promise of life to come.

Bodies of Water is an homage to The Wet season of the Top End. How did this series come about?

Well it was the wet season haha – but more seriously, it was about how The Wet is like an entity that covers the landscape; a blanket of life that smothers everything that came before.

I find it impossible to not be inspired by it. Water also means danger in the Top End. “Stay away from the water”, is something parents find themselves repeating daily. When I was small I refused to go kayaking in a dam in NSW because the water was murky and I thought it would be full of crocs. The water is life and death all at once.

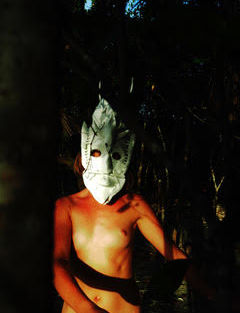

What’s the story behind the work ‘Kiss of Death’ which shows you with a crocodile?

This crocodile was found dead by the Mimal Rangers while recording buffalo damage on country.

I have never had to explain my work to Indigenous Australians; they are usually the first to understand. Before I made self-portraits I made a series called Burial Rites which was about honouring the lives of dead animals by creating arrangements for them in the environment, photographing them and burying them. Aboriginal people often brought me animals they found in the environment. Like it was the most natural thing in the world “worro dead one” - even as a child I cared for snakes, magpie geese, eagles and many other creatures that Aboriginal people in Maningrida had given me as pets or because they were injured.

I will also say that I have always been very comfortable in the presence of death. I owe that acceptance to my family in Maningrida who walked us non-indigenous people through all the rituals of grief for the last 50 years.

I wanted this photoshoot to be a combination of the ideas of European belief systems of the underworld and Persephone combined with the environmental nature of death and drifting away both metaphorically and physically in bodies of water. The story of a goddess that comes from the underworld to collect the souls of the dead and returns them from whence they came.

Some of the river and billabong locations you work in are inhabited by salties (estuarine crocodiles). How does it feel to make work whilst sharing the environment with an apex predator.

What is the Territory without its crocodiles, hey? I think we underestimate just how much knowledge we have living up here, how much we read the landscape.

We all understand where to swim, where not to swim, when jellyfish are in the water, where we are prepared to take risks. Although I don’t underestimate the risks I take, they are also calculated and often come from a place of understanding. Although, sometimes, there is a bit of a ‘hope, pray and get out of the water’ thought process going on.

How do you hope your audience will interpret or engage with your work?

We can not protect what we are not connected to. I always want my work to ask the question: what is wrong with the dirt? Why am I worried about that water? What do I feel like when I see this image? I want people to rediscover their relationship with their own wilderness and to be able to feel it in their bones and then fight for it.

First Paris, now Darwin. What’s next for Violet Bond?

Although this year alone I have had work shown from Paris to Bucharest to New York and 16 other places in between, there is always something important about showing work here, at home, to people that know exactly how the red dirt feels on your skin, how dark water makes you nervous and what it’s like when you feel the first rain of the wet season.

Artworks on Sale

All photographic artworks listed below are for sale.

There are 10 editions total of each artwork.

You can choose from one of the following sizes should you wish to purchase:

A1: $495 (signed and edition of 10)

A0: $950 (signed and edition of 10)

A5 collection : $45 (signed and edition of 4)

If you wish to purchase an artwork, please pick a size and contact the gallery.

Email: info@nccart.com.au

Phone: +61 (08) 8981 5368